Seasonal weather conditions like calm winds and low temperatures are known to aggravate air pollution over north India at this time of year. But research suggests that increasing pollution has amplified some of these meteorological factors over the past few decades – which, in turn, may intensify smog further.

This pollution-weather loop is likely contributing to the current extreme haze in Delhi and other parts of the Indo-Gangetic plain, say experts. A study published last year showed that soot, black carbon and other kinds of aerosol pollution is magnifying the ‘temperature inversion’ effect often seen in winter, in which warm air traps colder air on the surface below, preventing pollution from dissipating. That’s because these aerosols have a warming effect on the lower troposphere – the lowest part of the atmosphere – while cooling the air on the surface below.

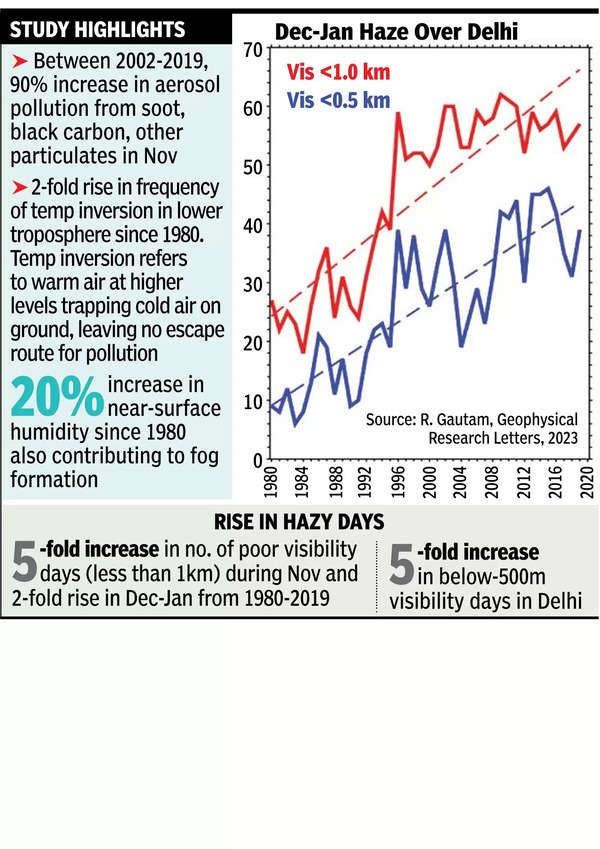

Aerosol pollution raises the stability of the lower troposphere and aggravates the temperature inversion that is happening naturally, said Ritesh Gautam, a senior researcher at Environmental Defence Fund in the US, who led the study along with NASA researchers. “This amplification effect seems to be strengthening decade on decade,” Gautam said. The study found a nine-fold increase since 1980 in the number of days when visibility is less than 500 metres during Nov. There was a five-old increase in such days in Dec-Jan, including in Delhi.

Researchers looked at data over four decades to understand the interaction of pollution and atmosphere over the Indo-Gangetic plain. They found aerosol pollution in Nov increased by around 90% between 2002 and 2019, likely due to the rise of crop burning. Exceptionally high aerosol pollution rose in Dec-Jan, too, by around 40%.

Those two decades saw a correspondingly large warming of the lower troposphere. The stability in this layer also showed an increase, with the height of the planetary boundary layer dropping since 1980. This layer acts like a dome confining the pollution to the ground, so any increase in its stability or decrease in its height would prolong or intensify smoggy conditions on the ground.

“The stability does not allow air to move out,” said S N Tripathi, a senior scientist at IIT Kanpur. Another factor is increased relative humidity, perhaps due to increased irrigation. More moisture in the air means more droplets of fog or smog can form. The study found a 20% rise in surface humidity since 1980.

All these factors are coming together to create a “multiple whammy” for Delhi and other parts of north India, said Gautam. “You can’t control the weather, but you can control the amount of pollution that is combining with the weather to produce this severe smog,” he said.

The physics of this feedback cycle between pollution and atmospheric stability is known, but Gautam’s study provides evidence of its effect over time, said Tripathi, who was not involved in that study. The long-term rise in lower tropospheric stability and relative humidity is also due to climate variability, said Chandra Venkatraman, an aerosol specialist at IIT Bombay. How much this meteorological change contributes to extreme smog is unclear.

Emissions remain the main driver of pollution, she noted. “Unabated emissions and increased secondary aerosol production under high stability and relative humidity conditions is leading to the extreme PM2.5 conditions over north India and Pakistan,” she said. Transboundary pollution may also be playing a role in Delhi’s current crisis, said Tripathi, adding that there seems to be a large pollution spike over Lahore.